This month we shine a spotlight on Elisabeth Hauptmann, a creative force behind several of Kurt Weill’s best-known German works. Hauptmann was born on June 20, 1897 in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia to an affluent physician and his German-American wife. Elisabeth was taught with her siblings at home, where they were given music and language lessons and performed their own plays. In 1918, Hauptmann became a teacher for wealthy military families in Germany’s rural eastern provinces. However, she loathed the hierarchical power structure and politics of the conservative Junker society. In 1922, Hauptmann moved to Berlin to embark on a new life immersed in liberal Weimar culture.

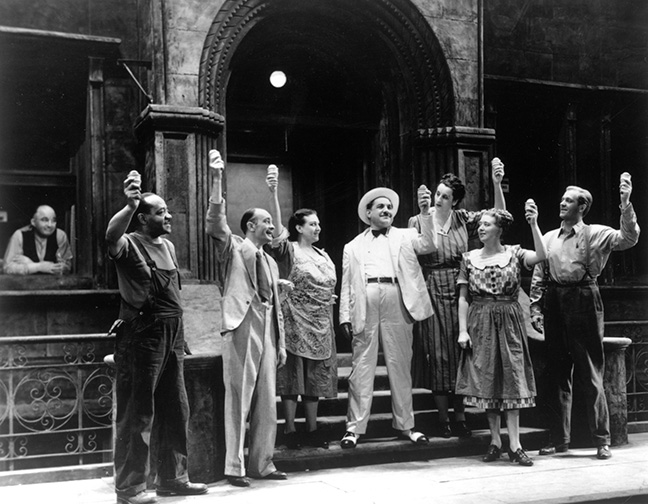

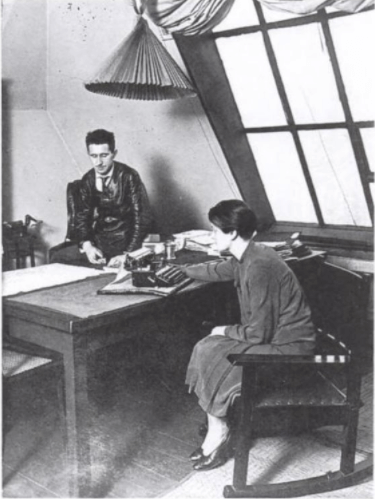

Hauptmann’s fluency in English and French enabled her emergence as a gifted translator. In 1924, she began working as an assistant to Bertolt Brecht, helping him to research and develop his ideas and also scouting for interesting material to adapt. In 1927, she came across an eighteenth-century “ballad opera” called The Beggar’s Opera that had been revived recently in London with great success. Hauptmann introduced Brecht to the piece, translated John Gay’s English libretto into German, and then collaborated with Weill and Brecht in adapting it as Die Dreigroschenoper (The Threepenny Opera). Brecht, Weill, and Hauptmann’s collaboration continued with a string of influential works that include Happy End (where her authorship was credited under the pseudonym Dorothy Lane), Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny, and Der Jasager. Many scholars have pointed out that these works could not have been completed without her; for instance, her co-authorship of “Alabama Song” and “Benares Song” is now an established fact verified by her annotations on copies of the draft lyrics. After all, Hauptmann was the only member of the triumvirate who could read and write in English.

In February 1933, the rise of fascism disrupted her collaboration with Brecht. Hauptmann remained in Berlin to save their manuscripts from confiscation. She was arrested for interrogation later that year. Upon release, she left for Paris, where Brecht and many other German intellectuals waited. In 1934, Hauptmann moved to St. Louis to live with her sister “for a few months,” while supporting Brecht’s literary ventures and teaching German to local students. In 1948, she moved back to Germany with her new husband, German composer Paul Dessau, who also collaborated with Brecht and composed incidental music for his productions. After Brecht’s death in 1956, Hauptmann served as his literary executor for the German publishing house Suhrkamp Verlag. She also worked as a dramaturg for the Berliner Ensemble, which had been established by Brecht and his wife Helene Weigel.

Hauptmann’s contributions to the Brecht-Weill canon went mostly unrecognized during her lifetime. A collection of autobiographical stories titled Julia ohne Romeo (Julia without Romeo) was published in 1977, four years after her death.

Elisabeth Hauptmann, the invaluable collaborator